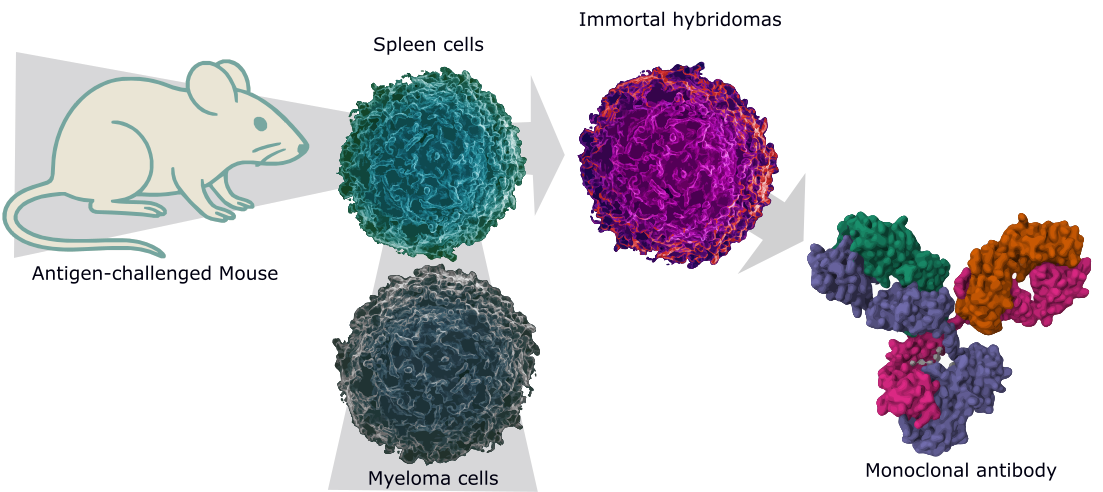

Fifty Years of Precision: The Antibody Discovery That Rewired Modern MedicineFifty years ago, Georges Köhler and César Milstein published a short paper in Nature. Few could have guessed that their hybrid cell experiment would seed an entire industry—one that today powers everything from cancer immunotherapy to COVID-19 diagnostics. What began as a clever laboratory trick has since transformed both basic research and modern medicine. Today, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) play a central role in how we study biology, diagnose diseases, and design life-saving therapies. From Lab Curiosity to Scientific StapleThe original insight was deceptively simple: fuse an antibody-producing immune cell with a myeloma cell (a type of cancer) to create a hybrid that grows indefinitely while secreting a single kind of antibody.  Immortal hybridomas can be created by combining cells from a mouse with myeloma cells. The hybridomas produce the monoclonal antibodies. (Antibody image created by molstar and traced by vtracer; b-lymphocyte from wikimedia, traced by vtracer. Image assembled using inkscape.) (CC BY-SA 4.0) This innovation solved two significant challenges at once:

Almost overnight, antibodies went from fragile, scarce reagents to dependable tools. Transforming Research and DiagnosticsIn laboratories worldwide, monoclonal antibodies quickly became indispensable:

Their reproducibility meant experiments could finally be compared across labs and over time—an enormous boost to scientific rigor. From Bench to BedsideThe clinical impact has been even more striking. Monoclonal antibodies are now approved therapies across a wide range of conditions:

Their strength lies in their specificity: unlike traditional small molecules, which often hit multiple targets, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) can be engineered to bind only the molecule of interest—minimizing collateral damage. Lessons in Scientific CultureThe Nature editorial marking this milestone emphasizes another lesson: breakthroughs thrive in a culture of open ideas and collaboration. The 1975 discovery was not the result of top-down programs or guarded secrecy, but of a vibrant scientific ecosystem where researchers shared, challenged, and built upon one another’s ideas. It’s a reminder that the environment in which science happens is as critical as the experiments themselves. Challenges and Next FrontiersDespite their success, monoclonal antibodies face ongoing hurdles:

Why It Matters NowHalf a century later, monoclonal antibodies are not relics of past innovation—they remain at the cutting edge of biotechnology. Their story illustrates three enduring truths:

Fifty years on, monoclonal antibodies still teach us the same lesson: true innovation begins with curiosity - and thrives when knowledge is shared. |